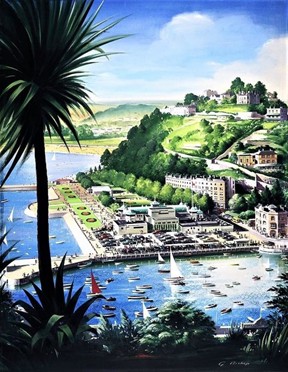

Torquay is a distinctive place.

All communities are shaped by both their past and by their local geography. But while we recognise that every town and village has its own uniqueness, places on the edge of the sea are different.

The idea is that beaches, cliffs, man-made harbours and piers are liminal places, meeting points between land and sea, and between civilisation and watery wilderness.

As a tourist resort Torquay is a place of constant movement and exchange with encounters, arrivings and leavings reflecting the tidal ebb and flow. The coast is also a messy kind of boundary, representing constant change, both in a physical sense and in the psychology of its inhabitants and visitors.

This is not an accident. The town was created to accentuate a sense of otherness by severing the link with the everyday. The aspiration was to attract outsiders by presenting an array of favourable impressions.

This was achieved through a grab bag of architectural styles: an Italianate tower in the Old Town Hall; Renaissance revival in the New Town Hall; an Art Nouveau Pavilion; the Scala, modelled on Milan’s Opera House; the mock French chateau of a railway station. All against a background of Tuscan villas, and later Spanish haciendas, Mediterranean apartment blocks, and hybrid Anglo-Indian bungalows.

“Look at the sea. What does it care about offences?” Torquay visitor James Joyce

The arrival of the railways in 1848 introduced a new type of industry, mass tourism. Yet, at the same time as welcoming visitors and their spending power, the democratisation of leisure intensified concerns about how to control and order holidaymakers. Torquay had long established itself at the pinnacle of Britain’s hierarchy of 27 resorts and intended to maintain that position. Blackpool and Margate could go down-market, but not Torquay. One solution was to consciously divert working class tourists and rowdy day trippers to alternative, affordable, and supposedly more permissive resorts, such as Paignton.

A further challenge to order came with a much-increased population which accelerated the growth of Torquay’s urban working-class, a community perceived as being prone to immorality, indiscipline and occasional rioting.

In 1867 the local newspaper, for example, reported that, “On Easter Monday Lower Union Street was obstructed by stalls and swinging boats were in great request. On Tuesday Torre Square and East Street were blocked up with swing boats, caravans, shows and sweet stalls.”

ABOVE: Torquay severed the link with the everyday: a chippy in an opera house

In other places such boisterousness could be ignored or regulated, but not in a place which based itself on hierarchy, order and deference. “The disorders to which the fair gave rise compelled the Local Board of Health to take decisive measures. And they accordingly directed the police to prevent the thoroughfares from being disrupted. So the fairs were extinguished.”

Indeed, a recurring theme in Torquay is of gatekeepers in the Church, politics and the larger hotels joining forces to enforce standards. In contrast, entrepreneurs and artists were always testing boundaries and searching for the kinds of innovation that would entice the easily bored tourist.

By way of illustration we have the effective banning in 1979 of Monty Python’s ‘The Life of Brian’in order, according to a Council spokeswoman, "to protect the people in Torbay". You had to travel to the inland fleshpots of Newton Abbot to see the film.

Despite ongoing efforts to maintain standards, resorts are where even the most conventional of folk show their racier side; somewhere the rules of people’s hometowns no longer apply. Resorts have then always been the setting for brief romantic interludes and transactional sexual liaisons. What happens in Torquay, stays in Torquay.

“Here by the sea and sand, nothing ever goes as planned” , The Who played in Torquay Town Hall on 27 August 1965

For almost two centuries Torquay was dominated by the tourist industry, and this made the town starkly seasonal, a town of two distinct halves. The summer months were an arena for hedonism and opportunity but at the close of the season the crowds rapidly disappeared, leaving the promenade and hotels unsettlingly devoid of life. Such an alternative aesthetic of eeriness, unease and nostalgia became an environment for fantastical encounters; and maybe a reason why more people claim to have had a supernatural experience in Torquay than anywhere else in Britain.

Ever since the late eighteenth-century, playwrights, authors and movie makers have recognised the liminal coast and used resort towns to portray extremes of emotion, experience and personal discovery.

ABOVE: Resort for brief liaisons where it was permissible to walk around in a state of undress

Specifically, the more astute social commentators have utilised the holiday experience and its abbreviated coming together of classes and genders to explore social change. George Bernard Shaw’s 1897 play ‘You Never Can Tell’, for instance, was set in Torquay and explores the battle of the sexes, the absurdities of marriage and the generation gap.

Change is an ongoing topic in seaside fictions. In the 1964 Oliver Reed movie ‘The System’ we see a bridge from the social realism ‘kitchen sink’ dramas of the late 1950s to a peculiarly British escapism; though with its protagonists still constrained by class in the ‘Little London’ of Torquay. It made an impact locally, nationally and internationally though its portrayal of radical changes in social and sexual politics. The movie also depicted the sojourn by the sea, promoting the Bay as a kind of British San Francisco for an emerging alternative society.

A lifestyle that was fast disappearing features in Ray Winstone’s 1979 movie ‘That Summer’, a slight story of young people visiting Torquay for employment and adventure. Yet, by the time ‘That Summer’ was released Torquay was changing again. Rising living standards, car ownership, and falling airline prices were leaving traditional tourist towns progressively less popular. Many coastal resorts then became symbols of national decline, that out-of-season ennui becoming, for some, an all-year-round existence.

"At the beach - time you enjoyed wasting, is not wasted," Torquay visitor TS Eliot

Throughout the decades Torquay has responded chameleon-like to the demands of the paying visitor. It has successively been a replica of the Tuscan countryside, a facsimile French coast, a refuge for the rich consumptive, a winter resort for the aristocrat, an upper middle-class retreat, a summer bucket-and-spade vacation, and a coach trip destination for the mature and pennywise. Other realities were to be found in the alleys and estates behind the gentrified shoreline. We await the next incarnation.

Much of what Torquay presents to the world is therefore skilful mimicry or illusory, the consequence of the stories it tells itself and to tourists.

ABOVE: Torquay is a grab bag of architectural styles

As a matter of course, all resorts fashion their mythology to promote and defend a constructed self-image. Central to Torquay’s identity is of being Britain’s premier destination, even though the Bay’s tourism sector accounts for only 9% of local employment. The largest employment sector is the more mundane ‘human health and social work’ at over 20%, followed by ‘retail’ at 17%.

The other selling point is of Torquay as a place of wellbeing. Since 1894 Torquay’s motto has been ‘Salus et Felicitas’, or ‘Health and Happiness’, recognising the nineteenth-century health spa and the modern tourist resort, the best of both elite tourist worlds. Certainly, coastal proximity does increase the chances of being fitter and healthier due to opportunities for physical activity alongside the positive effects on mental health of living by the sea. Resorts are, however, among the most deprived and sickest towns in the country, with levels of economic and social deprivation often exceeding those of the inner cities.

We then have an ongoing interplay between Torquay’s upbeat self-promotion and the lived realities of many residents.

Hence, the idea of Torquay as a liminal place persists. Not just a meeting point between land and sea, but a geography and a culture that shapes how we behave and how we see the world.

-1769768258322.jpg)