Milan’s eighteenth-century La Scala opera house provided the inspiration for Torquay’s 1909 Scala

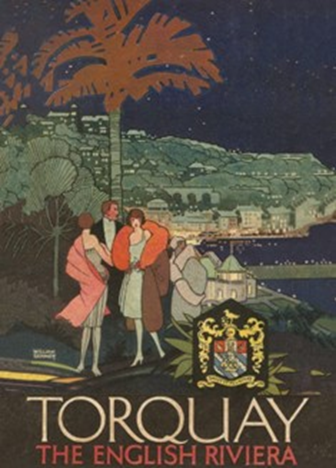

We know Torbay as the English Riviera.

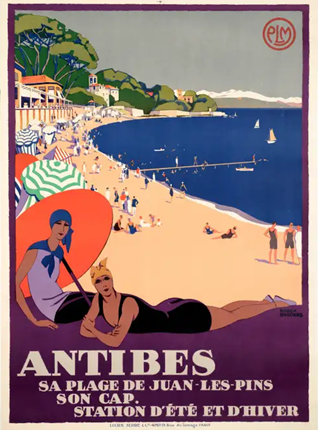

But why did we recreate the Gallic Côte d'Azur in an obscure bay on the south coast of England? And who thought that, in rural Devonshire, it was a good idea to counterfeit Cannes, simulate St. Tropez, emulate Antibes, or mimic Monaco?

One answer is that we have always reminded visitors of other places.

In the early nineteenth century, a notably impressed tourist remarked: “It is not England, but a bit of sunny Italy taken bodily from its rugged coast and placed here amid the green places and the pleasant pastoral lanes of beautiful Devon.”

By 1850 the nascent resort was even calling itself “the Montpellier of England”, while in 1862 Charles Dickens remarked: “Torquay is a pretty place... a mixture of Hastings and Tunbridge Wells and little bits of the hills about Naples.”

The polymath John Ruskin would carry on the theme and call Torquay “the Italy of England”.

From the early 1800s we’ve not only been comparing ourselves to the natural beauty of the Mediterranean but modelling our architecture, flora, and placenames on a coastline so very far away. At one time, we even put up bilingual English/French road signs for the passengers of the ferry ‘La Duchess de Bretagne’ on its often turbulent 4-hour trip from Cherbourg.

Torquay, as a consequence, is a grab bag of architectural styles on a surreal Monopoly board: an Italianate campanile tower in the Old Town Hall; Renaissance revival in the New Town Hall; an Art Nouveau Pavilion; the Scala, modelled on Milan’s Opera House; the mock French chateau of a railway station. All against a background of Tuscan villas, Spanish haciendas, Mediterranean apartment blocks, and hybrid Anglo-Indian bungalows.

Milan’s eighteenth-century La Scala opera house provided the inspiration for Torquay’s 1909 Scala

Milan’s eighteenth-century La Scala opera house provided the inspiration for Torquay’s 1909 Scala

On the other hand, we never really went full continental.

We may build esplanades and promenades to replicate those of the Mediterranean resorts, but with sensible shelters for the inevitable blasts of wind and rain. And though we imported café culture to the Strand, Anglo-Saxon beer guzzling and southern European wine-drinking remain uneasy bedfellows. One wag even noted that the further up Fleet Street, the more likely cappuccino becomes anglicised into ‘frothy coffee’, latte into ‘milky coffee’, and mochaccino into ‘choccy coffee’.

Torquay increasingly came to resemble the resorts of southern Europe as the town was selected, designed and promoted to emulate the attractions of the Rivieras of Italy and France. Hence, the English Riviera, adopted from the Italian noun for ‘coastline’.

The genesis of Torquay, and the origins of its multiple and conflicting personalities, lay back in the era of the Grand Tour. This was a time when Britain’s youthful elite scoured the continent in search of sexual adventures, alcohol, and opium; with perhaps the occasional visit to something cultural. When they returned to their homeland, they replicated what they had seen.

The Mediterranean’s mild climate had already made the French Mediterranean a favourite winter haven for European aristocrats. These vacationers were soon joined by a British contingent attracted by Tobias Smollett’s 1765 book ‘Travels through France and Italy’. The Scottish doctor John Brown further prescribed ‘climato-therapy’ as a cure for tuberculosis, giving Nice “a colony of pale and listless English women and listless sons of nobility near death”.

Meanwhile, back in somewhat less-sunny England, Torquay was similarly catering for the sick and dying. In 1817 it was remarked that Torquay “was built to accommodate invalids”. By 1840 the town was an “asylum for diseased lungs”, the hotels “filled with spitting pots and echoing to the sounds of cavernous coughs”.

Entrepreneurs, however, had long recognised the money-making potential of both places. But what really transformed these fishing and farming communities into cosmopolitan resort towns was the arrival of the railway; Torquay’s first station opened in 1848 while Cannes’, for instance, came in 1863. This hugely improved connectivity catalysed the development of luxury hotels, entertainment venues and coastal mansions. It also gave the Bay that peculiarly British and malleable of dwellings, the villa.

Both resorts were therefore able to take advantage of the late nineteenth century Belle Époque, the ‘Beautiful Era’, a period of imperial expansion but regional peace, optimism, economic prosperity, and technological, scientific and cultural innovation.

Recognising overseas success, Torquay time and again looked to its French counterpart for inspiration. One example that had a profound impact on our staid Edwardian town came in 1923 when iconic French designer Coco Chanel mistakenly caught the sun and displayed bronzed skin.

Her friend, Prince Jean-Louis de Faucigny-Lucigne, pronounced: “I think she may have invented sunbathing.”

Acquiring a tan then rapidly became a way to display modernity and proclaim fashionable youthfulness. French beachside resorts then started to remain open throughout the summer, their usual off-season. By the mid-1920s sunbathing had likewise become a health craze in Torquay. Continental styles and attitudes quickly transformed beach fashion, generated a summer season and reshaped our local architecture, with balconies and sun terraces designed to facilitate sunbathing.

Yet, while we do see Torbay copying its French counterparts, especially during times of economic uncertainty, sometimes those attempts don’t end well. Take Torquay’s failed experiment with casino culture.

By the late 1960s Britain’s traditional seaside resorts were worried that their business model was beginning to fail as overseas holidays, car ownership, and holiday camps were offering more vacationing options.

Once more, the French seemed to have an answer to decline. After opening in 1863 Monte Carlo’s casino quickly became a magnet for Europe’s wealthy elite, its massive profits even allowing the principality to abolish taxation. This hadn’t gone unnoticed across the Channel and so Torquay looked at upmarket gambling to reinvent itself, to attract major investment, and to charm a new upmarket visitor-base. There was even talk of a Torquay International Airport to fly in all those high rollers to casinos in the Pavilion and Oldway Mansion.

Then, on December 21, 1973, six people were shot, four being killed, at Torquay’s Carlton Casino. The casino mirage vanished soon after.

The decline of Britain’s coastal resorts in the late twentieth century is well known.

In contrast, the French Riviera is now one of the most dynamic regions in Europe, a place of luxury, glamorous parties, and exclusive resorts catering to a global elite. Commonplace are brand name stores such as Gucci, Cartier, Chanel and Dior. Less so in Union Street and Hyde Road.

The provincial French are suitably proud of their artistic and cultural heritage and exploit the world-famous imagery of those who made their homes in the region, such as Picasso, Matisse, and Chagall. Though Torbay surely wins the literary Top Trumps with Agatha Christie.

Torbay can’t, of course, claim as long a list of notable residents as our French counterparts; Johnny Depp, Elton John, and Bono seemingly not having found a reason to relocate from their Mediterranean mansions. On the other hand, we remain proud to have welcomed Larry Grayson, Ruby Murray, and the Krankies…

That the English and French Rivieras have followed different paths was most probably inevitable and not all a bad thing. The Bay would be a far different place had big money, with all that involved, targeted our communities. As English writer Somerset Maugham recognised of his adopted French home, the Côte d'Azur is “a sunny place for shady people”.

And so, while both Rivieras grew from being rural backwaters into sophisticated holiday destinations, we shouldn’t make too many other parallels. After all, it’s an 83-mile drive between Monaco and St Tropez, a region with a population of over a million people; Babbacombe to Brixham is only 10 miles and we only number 140,000.

Perhaps the idea of reflecting resorts may now be little more than a marketing myth that we should discard. Or maybe we should take pride in being the Riviera that never sold out to the billionaires?

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.